Wikicliki: In Conversation with Debbie Ding

01 Sep 2022

Since 2008, artist Debbie Ding has maintained Wikicliki, or http://dbbd.sg/wiki, a constantly evolving work of art that traces emerging issues around society’s use of the internet, technology, design, architecture, linguistics and varied culture/theory topics. The following conversation is excerpted and edited from a public talk on 29 May 2021, where Ding and SAM curator Shabbir Hussain Mustafa trace key moments in the former’s practice and discuss how the “success” or “notability” of contemporary artworks can be measured, especially as they become increasingly dematerialised.

The exhibition is named after your work Wikicliki. But interestingly, the artwork itself does not appear in the exhibition in a more formal presentation format. This is what we were trying to think of, as a curatorium: what does it mean to collect? What does it mean to engage with collecting habits at a time when smartphones and contemporary technologies are so pervasive in our everyday lives? I thought Wikicliki is a great site for exploring some of these questions. Could you introduce the work?

The wiki, as you can see here [http://dbbd.sg/wiki], is a website that I’ve maintained since 2008. If you want to describe it by its technical components, it’s basically a customised version of Media Wiki, which is similar to Wikipedia. What Wikipedia runs on is a wiki software which is free to run on your own server. It runs on PHP and you can customise it the way you want. What I’ve done is, I’ve been building it over more than 10 years. Technically, as an object, you could say that what I’ve made is a customised copy of the wiki software. But of course, it’s also more than a piece of software. It’s a bit like an artist’s notebook. It’s kind of weird, because when you asked me about this as a work, I hadn’t really thought of it as a work. It acts as source material for me, where I have been putting all my notes, sometimes a bit personal, so they are all in there.

Then there is also this idea of the cult of “done.” For instance, once you publish it on the Internet, even if it is not done, it is considered done now. So, you can mentally close it off, and move on to the next project. I created the Wiki a bit like that – in a way, I publish things and notes, and once I have set it down, I can move on. But I can also search it like my second brain. If I’ve forgotten what I thought about something, I can search it back in my Wiki, from a few years later, and then realise that what I had thought about was totally different. That has always been interesting.

I also like it when I’m refreshing the webpage. When I scroll through it, there are lots of things that randomly happen to be put next to each other. The ideas sort of smash up, like when you go to a library, and you pick up different books on the bookshelf—the ones that just happen to be next to each other sometimes talk to one another. Similarly, there are unexpected connections made between the different entries for me. I made it also an attempt to learn coding in the beginning, because I used it to keep all my snippets, in a handy way. Nothing is ever really lost. Except when I lose source codes, like I indicated at the start of this conversation. But at least it helps me learn and refer back to things.

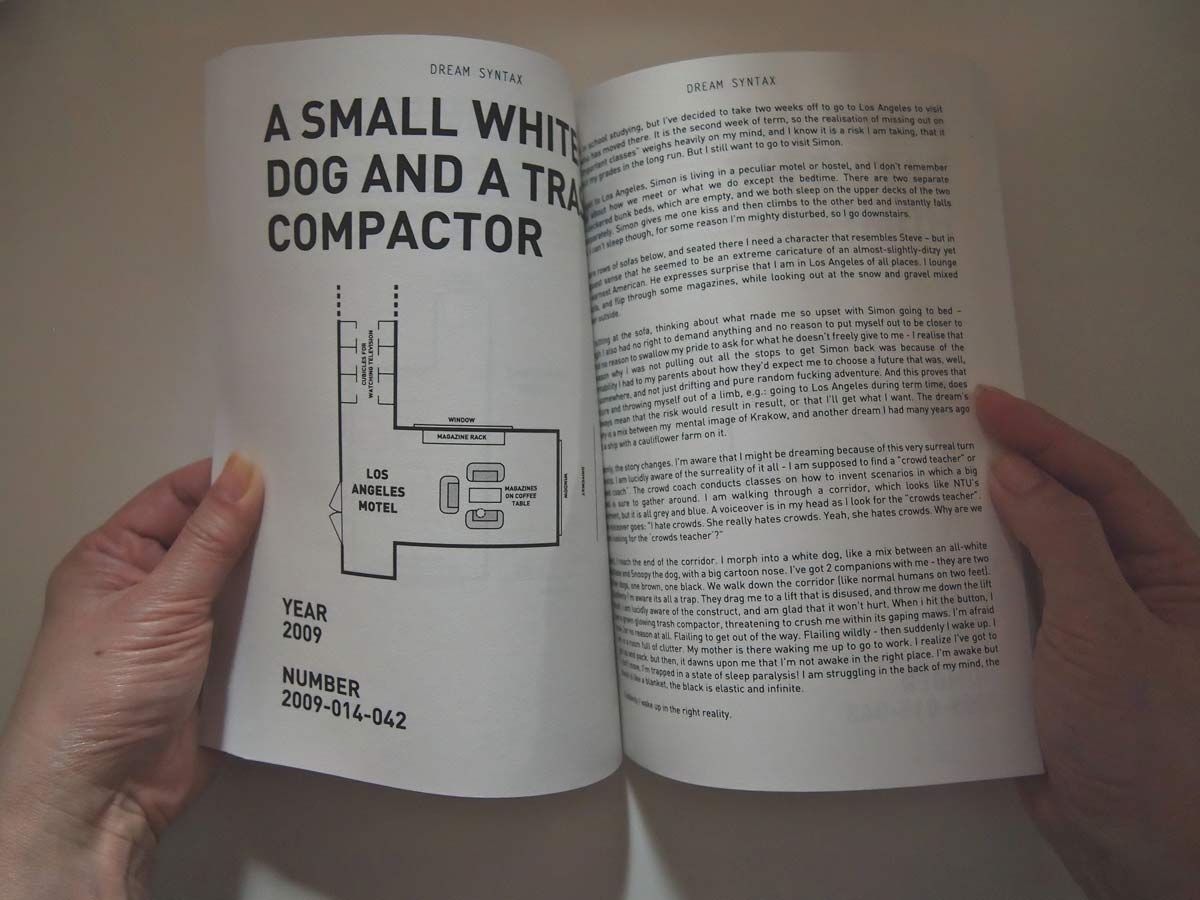

To return to an earlier aspect of your practice: walking. Through walking, you chance upon encounters that happen around the city. Sometimes it’s a moment waiting to reveal itself, and it only reveals itself through the act of walking and being somewhere, at that moment, and then having a dialogue with whatever you have found. I thought it would be interesting to recall some of those early works. Say, for instance, Dream Syntax, which you once described to me as a "kind of memory palace"...

It’s funny to talk about walking being a big part of my practice when, to be very frank, in the last few years, I haven’t really walked as much. But in the beginning, a lot of the works were about this kind of mapping, experiencing a city on the ground, as someone walking, and writing about walking. My degree was in literature, so I thought of myself as a writer, that I would be able to write whatever I wanted about cities, how I experienced cities, or also how I know/knew cities, through literature and books, and then getting a picture of what a city might look like. I also felt that I had the chance to write it into something else, write it even from black to white, if I wanted to.

A lot of those early works are this kind of writing and mapping. So maybe, I tried putting them into words. And then after that, making them into digital maps was a way of articulating this city as well. I think it is a “memory palace” because I also think of it as mnemonics, a way to remember a place even after the site/place/encounter is no longer there. Like when you wake up from a dream, that dream doesn’t exist anymore, that space ceases. But you can write it down on paper, you can draw a little map—as ways of capturing an experience that seems to colour your whole day. So, the early works were all about capturing this very intangible quality.

Here the River Lies is a work that begins around 2008, just after you graduated from NUS and you are doing quite a bit of walking and thinking. Could you talk a little bit about how it came about? And what were the impulses for the work itself?

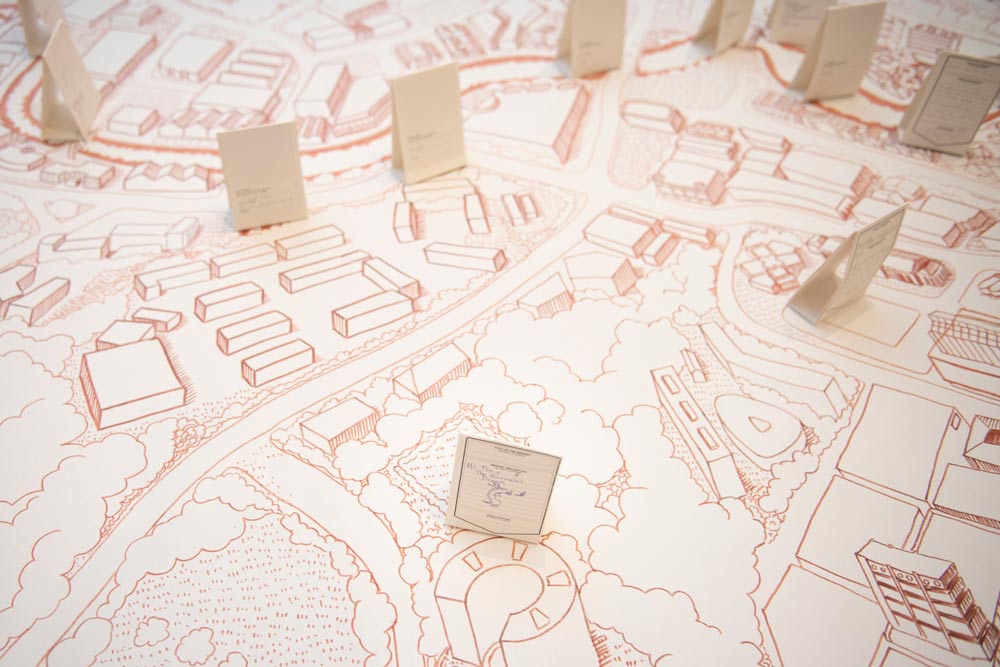

Here the River Lies and the works about the Singapore River start from a very simple question. When I asked people about the Singapore River, I realised they didn’t really know where it was. I worked in two buildings, which were near the River and spent a lot of time walking about the River. Every single day, I had to pick up a design brief on the other side of the River from my office building and the whole endeavour felt strange as I had to walk across the River. Living in Singapore, you would know what I mean, whereby ecology shifts within, above and under concrete. When I talked to people about it, such as friends or colleagues, not everybody seemed to know, or even register the River as a geographical feature.

I was used to the idea of thinking that a river is something you see and witness, because I also worked for some years in the UK. And over there, everybody knows what the River Thames looks like, because they see it in everything, in pictures, in postcards. But the Singapore River is something that people don’t seem to have much of a picture of. And so, I ended up making a series of works about the river, and I was interested also in the way the stories about it were quite mundane. I wanted to have an opportunity to collect the stories from people – these stories didn’t have to be ‘real’, even dreams were welcome. I was not interested in validating stories or details. I think around that time, there were a numerous projects unfolding, like the Singapore Memory Project. And some of these “memory projects” were very earnest, in a way that I didn’t like, because people were looking for “good memories” and “good stories.” These good stories sometimes precluded the bad memories, like ones that you can’t really say. Just like, “Oh, it was really bad. I’m not gonna tell you my bad story. Why am I going to tell you the worst time of my life? Why would I recount it for you and relive that trauma?”

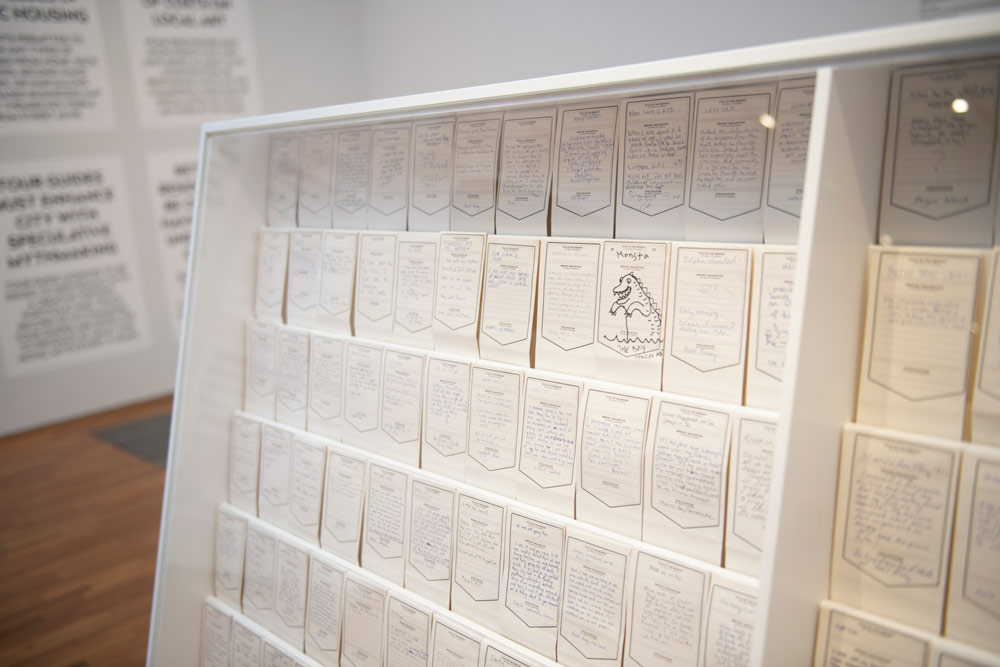

So being someone who likes to write stories, I wanted to collect such narratives from people. And this map of the Singapore River, which I drew out of memory, was one way to enable that. You probably noticed that though I have all these computers and digital matter around me now, I felt like I had to collect these stories in person as I did not want to lose the marginalia, all the things that people will throw, and write on the side, let’s say in a book or paper. And so Here the River Lies captures these stories differently. If I ask you to fill out a form, I know it wouldn’t be the same. And the fact that the entries are physical, they sort of stand out in the real gallery space. The entries are all randomly arranged and juxtaposed. When you read it, you read a few cards that are randomly arranged, and you almost piece the story together in your mind.

I wanted to get you to reflect a little bit on another aspect that is very much connected to your work. I think it’s called “version control” – tracking the object as time shifts, and as objects attempt to escape time as well. The reason why I raise this inquiry is connected to something that the Wikicliki exhibition attempts to unravel as well. Museological conventions, if I may call them that, when it comes to painting and sculpture, and even to some extent installations, have been established precisely to perform “version control.” So how does one conserve the work? How does one preserve it? How does one present it? There is a market for it, you know—how do these things circulate, change hands, provenance, and so on and so forth.

But when it comes to some of the works, even work such as yours, with regard to contemporary technologies, it’s not so self-evident, especially at this moment in time. Institutions, and even the art market, to some extent, are trying to figure this out. I was wondering if you could talk about this, but in relation to version control, and how this interacts with your work?

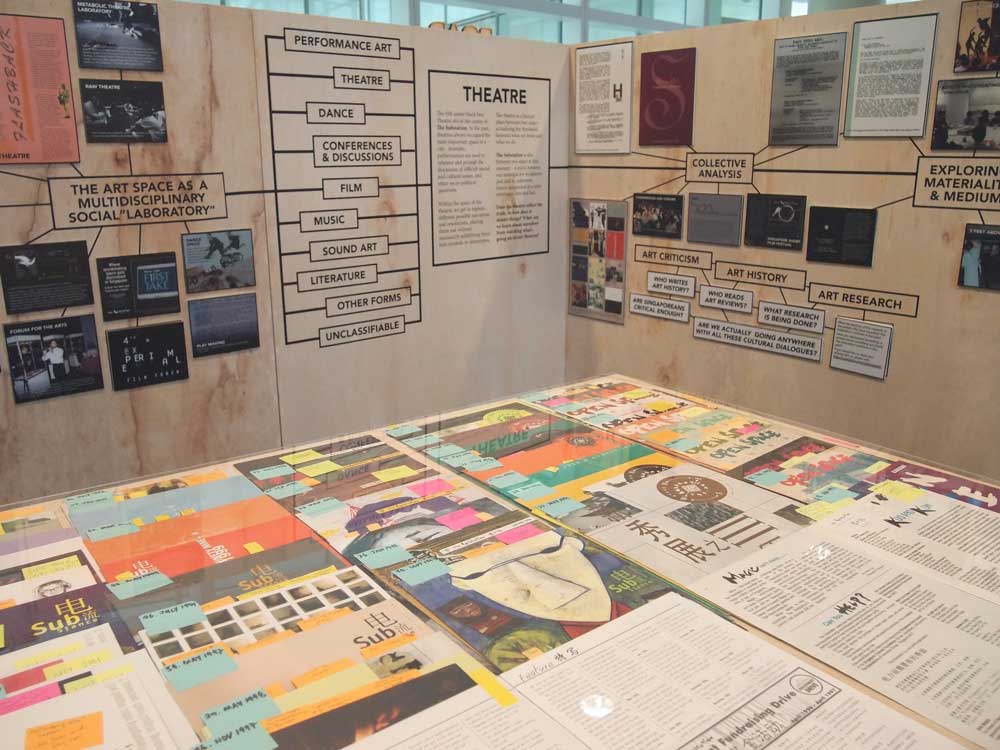

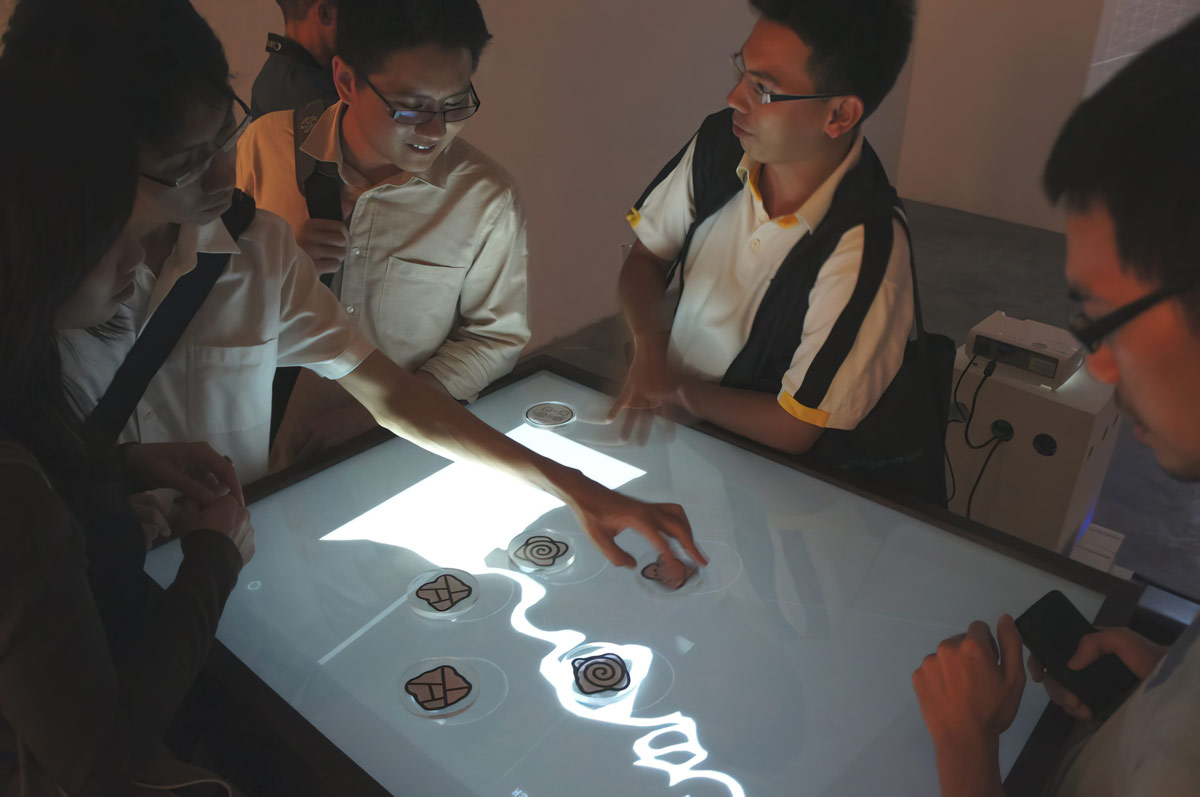

A lot of the works I made in the past have been about archiving. Here the River Lies is about archiving all these stories. I’ve worked on projects, like the Substation’s 25th anniversary, which involved going through their archives and trying to think of the fate of all these things an institution generated in its life. Even for my digital works, keeping all the code together has been surprisingly hard. I thought I would have all of it together. But even when we preparing for this exhibition, and I looked at some of the older works that I had made, for instance these touch tables from 2010 and 2011, I realised I don’t really have the code for them anymore. The technology used to make them was quite different. That was built in Flash in ActionScript 3. Flash is totally dead today. So, what happens to all these interactive works? Even for someone who was thinking about the archive, it was very hard to hold on to.

My master’s programme, Design Interactions, at the Royal College of Art, was quite a well-known programme that ran for 10 years, and I was from the last batch. I have a hard drive for some of the materials that were collected as part of the programme’s life over a 10-year period, including student work from 1995 onwards, years before it was even called “Design Interactions”. Some of the files were made on Mac OS versions that don’t even exist today, so you must get the emulator to access the files. Oh, and these works were made in such tiny resolutions, 600 by 400 pixels – so tiny by today’s standards. So how do you access it?

That’s one of the things that I’ve often struggled with.

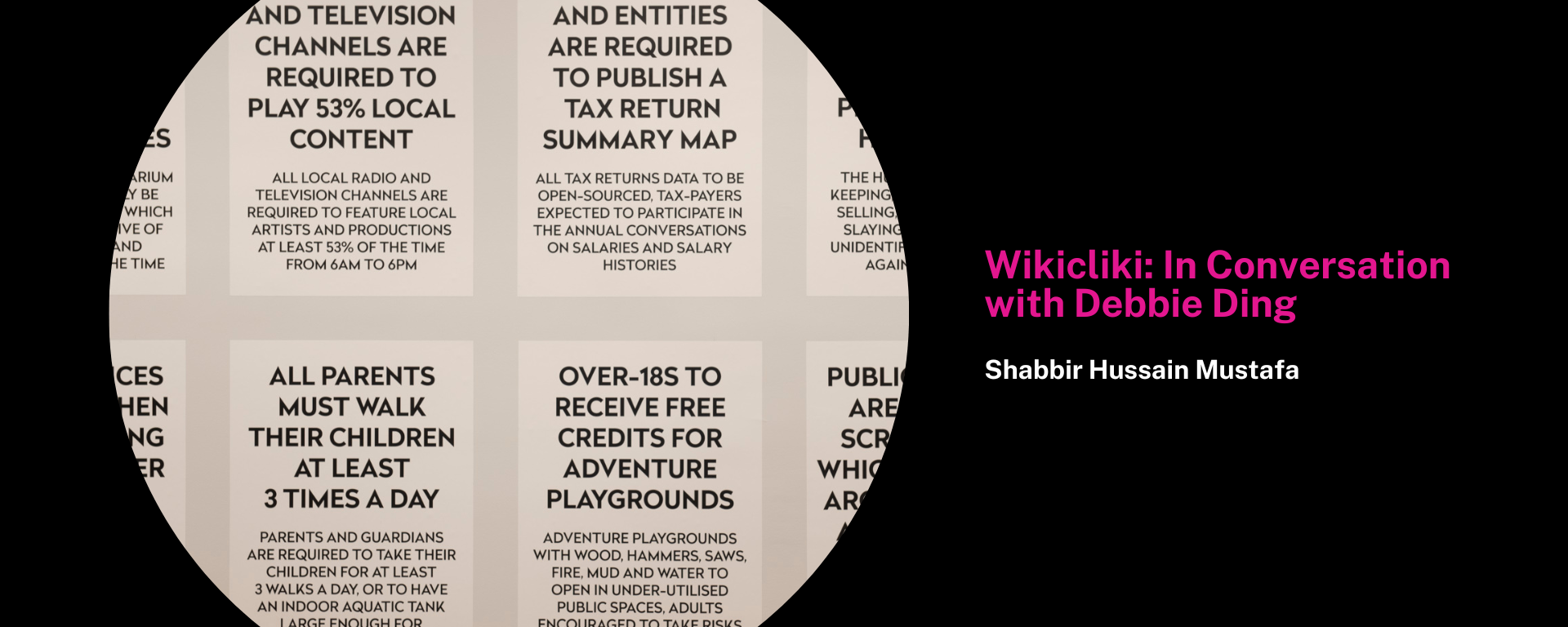

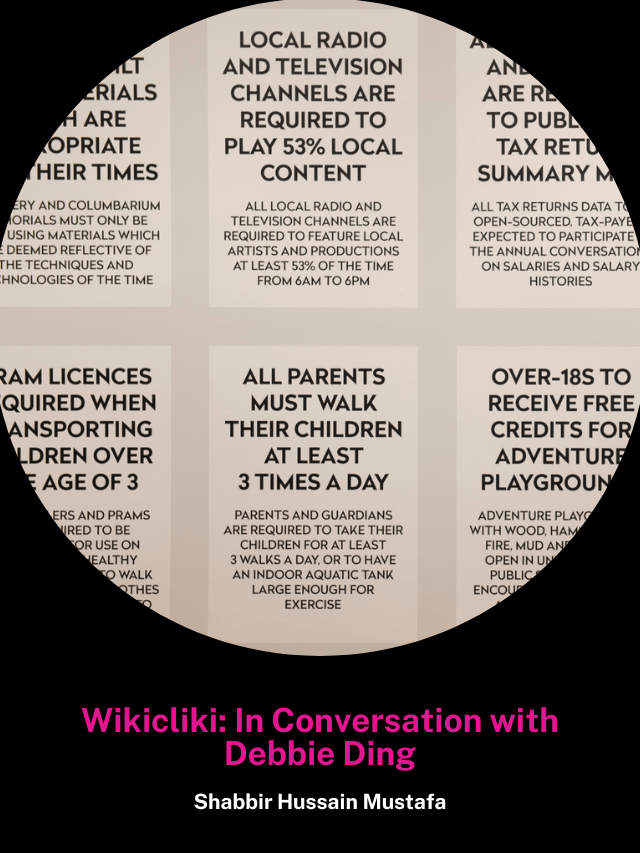

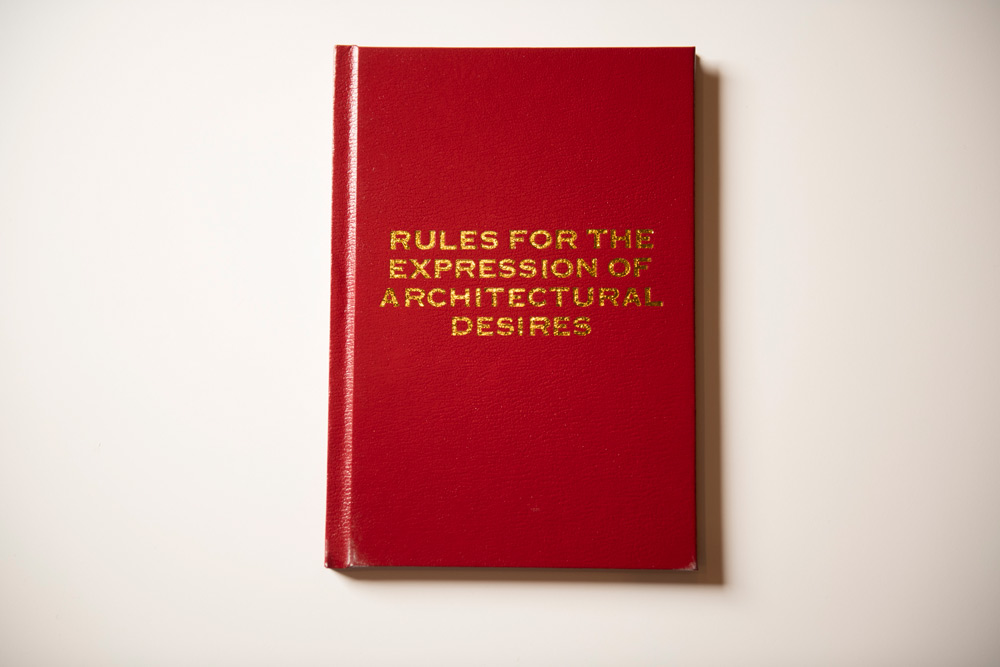

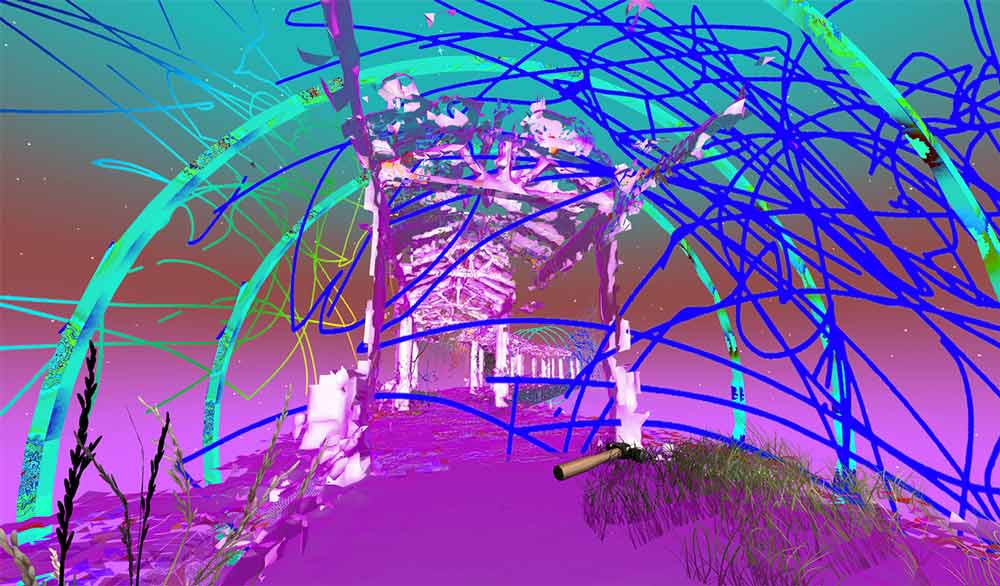

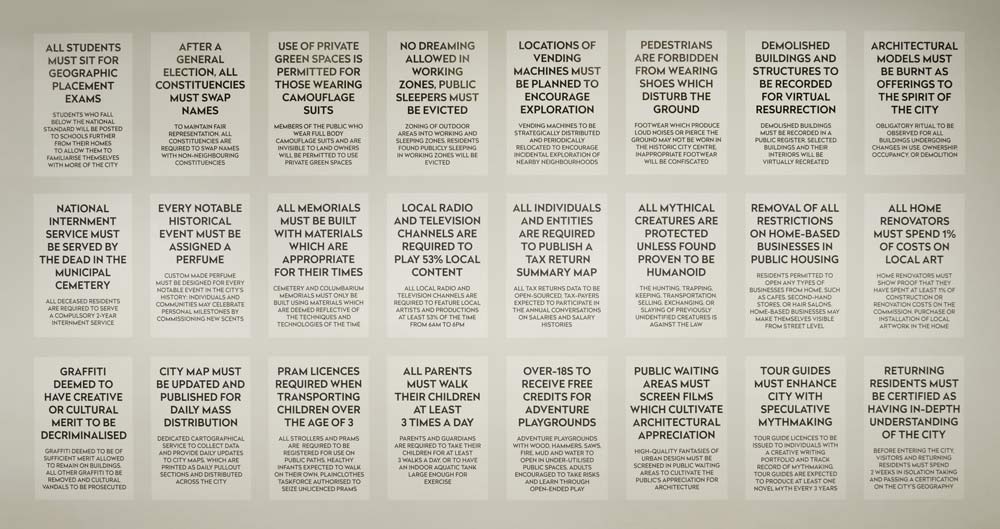

You can see this is the case even with Rules for the Expression of Architectural Desires. There are so many versions of this, and along the way I think I have lost the originals, and the code base for it as well. I’ve presented the large prints on the wall in many different sizes, in different colours. Sometimes when I’m asked to put down the manual of what this work will be like in the future, FOREVER, I ask myself, what is this work? How do I define the work in the contract or manual for documentation? It’s hard for me to say what the final thing is.

So just going back to some of the earlier points that we raised, especially with regard to prototyping, is it fair to say that your projects, especially Wikicliki, are prototypes that are never finished?

You could even say that I will conceivably continue editing Wikicliki while I’m alive. So, it would never be complete, unless I ceased to exist. And I mean, the point at which an artist decides a work is resolved sometimes feels very arbitrary. Whereas if I were dead, that would be a definite milestone.

This is where I think we should really talk about how a work such as this could potentially be minted as an NFT, and all the questions that potentially emerge because of that. Could this be actualised?

I suppose the point is that previously, if I told you I was going to sell you my Wiki, my customised Wiki code and its contents, I will probably have made a weird cardboard box and said, “This is the Wiki. This is the contract with the current Wiki.” That’s what people do, I guess. And that feels so weird, because it’s so analogue and so problematic to do it that way. But how do you know that’s the real thing? The whole point of the smart contract would be to provide that authenticity. Even though the thing is public on the internet, everybody could access it, this is the authentic version. But then it still has the problem that the Wiki has many versions like now, this is the version that is, as of today, which is 29 May at 1:53pm, this will be the version of it now. But then, if you were to have it tomorrow, would that be another version? Would that be a new version that could be minted as a separate one? How do you define that contract for what entails a digital work?

So what is the conundrum here? Is it about how we go about adding onto and visualising the blockchain itself?

I think it has more to do with the minting of NFTs. The thing is that, the NFT would claim that this was the authentic version of itself, the authentic unit of it, and it didn’t matter if you could provide a link to say this is the authentic version or not. Some of it could be also put in below. It’s very big. It couldn’t be put into the contract; but that no one else could own it, even though it’s public on the internet.

A quick question about this exploration of potentially minting mutability as an NFT. I think NFTs themselves also have all sorts of hierarchies, right? They’re not as democratic as they are made out to be, obviously.

Cost. There is also the ecological cost. Now you see a lot of people selling NFTs. There are marketplaces, but these marketplaces are kind of weird. To get into these marketplaces, there are still certain gatekeepers and barriers to entry. It is not fully living upto that dream of democratisation. Although I think there is still something special about the technology of smart contracts itself.

I have another question that’s come in from the audience, which is, “Would SAM acquire Wikicliki as an NFT?” I can try and answer that. Yes, certainly we can explore it for the collection. But how?

How will you show it? I mean, there may be very practical ways to show it, but of course, who comes up with these ways of showing a thing? Is this even a work? Are we standing in a work now, this game which is a Mac OS native app? The Legend of Debbie, the other project I’m working on, is a game. It’s also a game that exists in a few versions. There’s the Mac version of it, the Windows version of it, could there be a Web GL or Android app? There’re all these different versions of themselves as well. So, which one is the one to show?

One last question: “Are we at that point whereby there will be a break such that the blockchain will lead to a separation from the art world as currently understood, and chart its own autonomous path with its own markets, its own art history, its own institutions and its own gatekeepers?”

Is that what one should hope for? For an artist like myself, who hasn’t really worked with commercial galleries before, there’s always the question: What is the art market? Who is the art market? Where’s the art market? I have been working with institutions. So, when you ask me what is the art market, I find it quite hard to offer insights. To think of NFTs, then, I will also wonder who exactly is that buyer. To begin with, it’s probably a very different individual from those on the traditional art market, in terms of their motivation for collecting the art. So yes, I imagine it could be. At this point, it’s early to say, but I would be very happy if it produces a separate system after all. But one that improves on the way things are, that not only privileges those who are already really privileged. So, it doesn’t have any of those systemic injustices that also occur.

Debbie Ding (b. 1984) is a visual artist and technologist who reworks and reappropriates formal, qualitative approaches to collecting, labelling, organising, and interpreting assemblages of information. Through these explorations, Ding opens up possibilities for alternative constructions of knowledge.

Shabbir Hussain Mustafa is Senior Curator at the Singapore Art Museum.