Hidden In Plain Sight: The Historic Interiors of SAM

Housed in the former campuses of St. Joseph’s Institution (SJI) and Catholic High School (CHS), the Singapore Art Museum is steeped in architectural history. It shows not only on the facades of the buildings, which were developed across the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century but also their interiors which are often overshadowed by the art.

Architectural conservation specialist Ho Weng Hin sheds light on five lesser-known details his team at Studio Lapis uncovered during their on-going restoration of the buildings.

1. Look Up and Wunder...

Images courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Photographer Kate Pollard (left) and Studio Lapis (right)

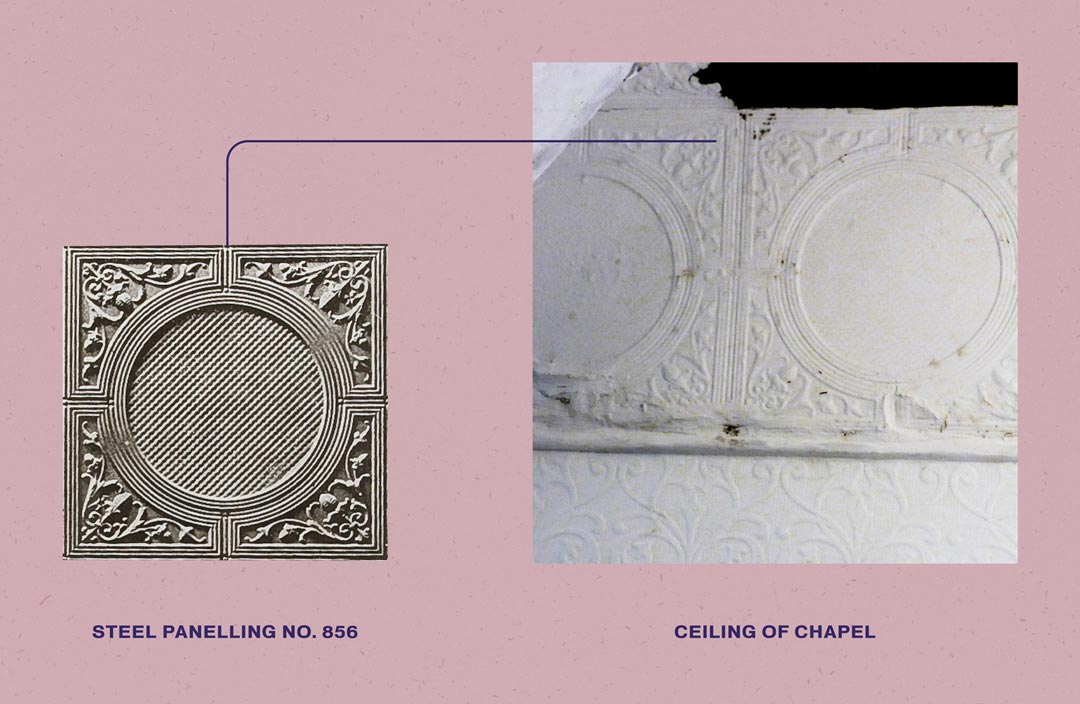

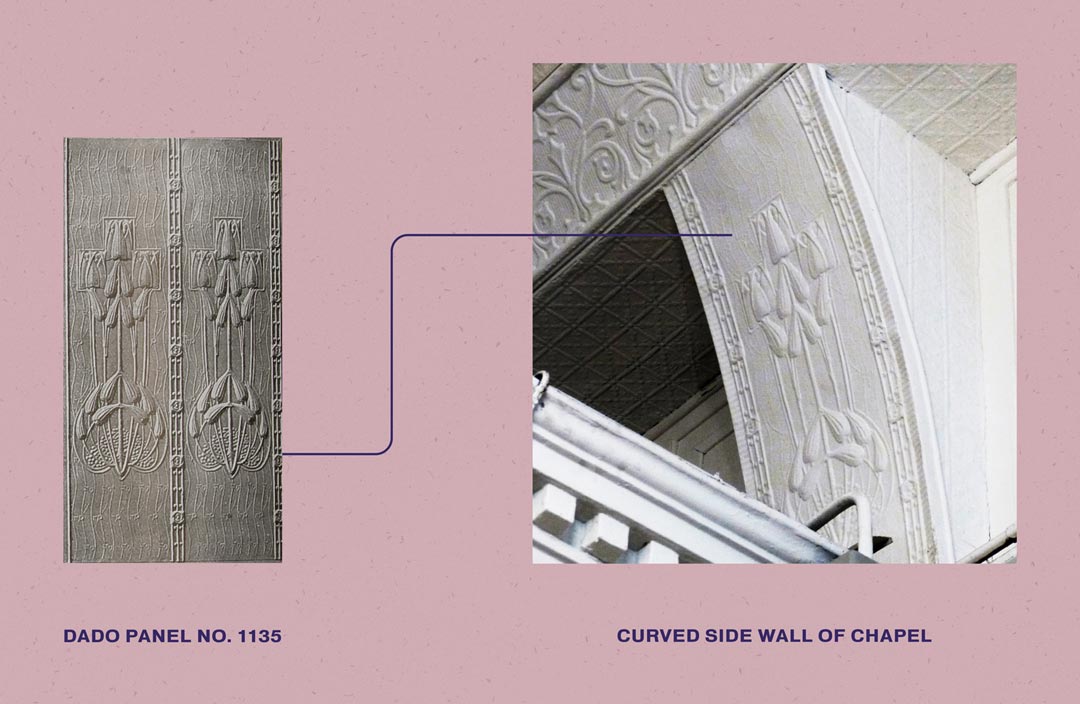

Built in 1912, the former chapel of SJI is highly-ornamented with its colourful floor tiles, intricate sculptures depicting the 14 Stations of the Cross and a stunning artwork by Filipino artist Roman Orlina. But often missed out are the stamped metal panels on its wall and ceiling — a rare find in Singapore. According to Weng Hin, similar examples exist only in the neighbouring Church of Saints Peter and Paul, and the Istana was also believed to once have metal ceilings too. “As you had to import them, you had to be quite well-endowed to afford it,” he says.

Images courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences. Photographer Kate Pollard (left) and Studio Lapis (right)

The chapel’s panels were from Australian manufacturer Wunderlich, and reflect the transition of building construction towards mechanisation in the early 20th century. Their finely wrought details were mass-produced by machines using hand-carved moulds. Despite the cost of shipping, such panels were an affordable alternative to hiring artisans who required months to manually sculpt ornamented stucco-work. A “wunder” building solution of the times!

2. Mystery of the Pink Chapel

Image courtesy of Studio Lapis, St. Joseph’s Institution (slide left or right to reveal the full-sized images)

When the old campuses were converted into a museum, their walls were painted over in white, the preferred neutral colour for exhibiting art. But it concealed their colourful pasts, including what was possibly SJI’s pink chapel! Why this colour for an all-boys congregation? Weng Hin speculates it was for religious reasons since the chapel was a site of worship for the Catholics who venerate Virgin Mary. He adds that photos of the chapel in the mid-nineties also show it painted in beige and deep orange schemes, “White is a late 1990s and 2000s obsession”.

3. Murals, Murals On the Wall

Images courtesy of Studio Lapis

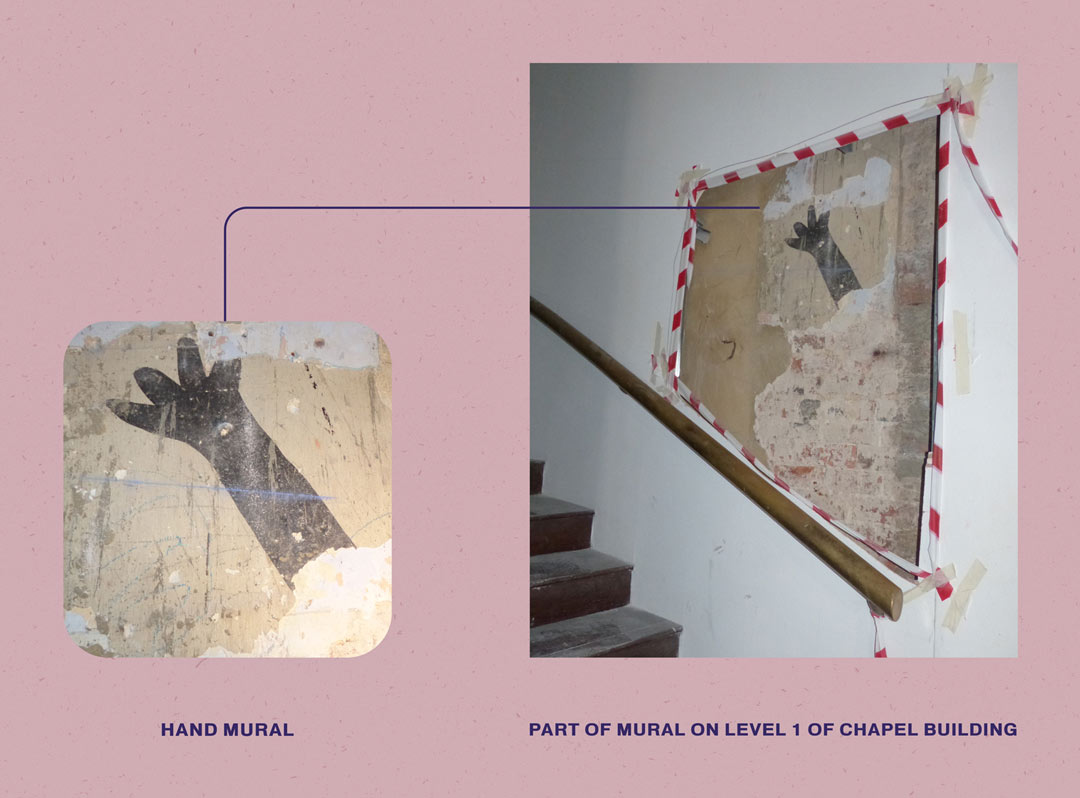

When the dry walls in SJI were removed for restoration, Weng Hin and his team uncovered traces of stencilled ornaments in shades of blue, red and ivory. Found along the mid-section and where the walls, ceilings and floors meet, they suggest an interior once decorated with murals. These probably date back to before the Second World War, says Weng Hin, and functioned similarly to the carved timber panels found in homes of the well-heeled—but on a budget. “It depicts simple and unpretentious efforts to elevate the space with a sense of decorum,” he says. “After all, there were so few of such schools built for the people at that time.”

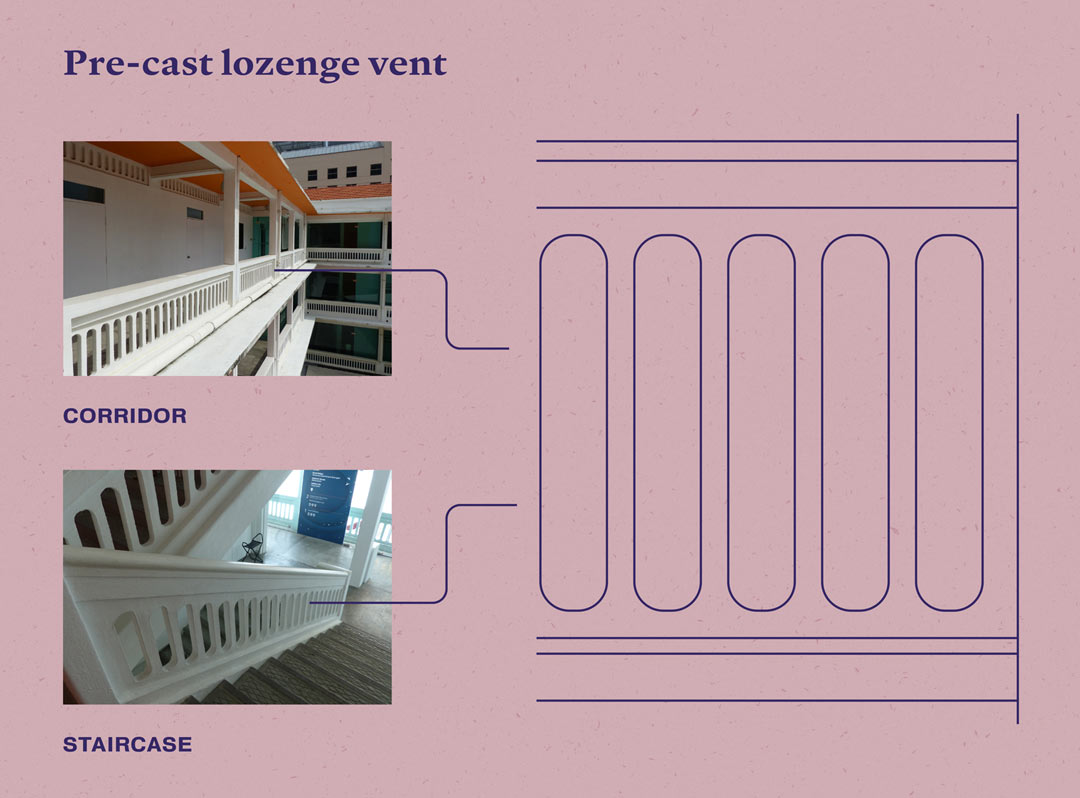

4. That Cool "Lozenge" Vent

Images courtesy of Studio Lapis

The former CHS looks modest because it was built after the Second World War when resources were limited. However, beauty still exists in its details. The four-storey building is wrapped with corridors of lozenge-shaped vents, which also line its staircase railings and the walls of its rooms. These precast elements were not just decorative but kept the interiors cool by facilitating cross-ventilation. They are an example of the “architecture of austerity” as architects sought to reduce wastage by paring down their buildings to just their functional features. “Wherever the architects can add ornamentation to add a sense of decorum or at least make the space a bit more interesting is through tiny details, and they are quite ingenious!” says Weng Hin.

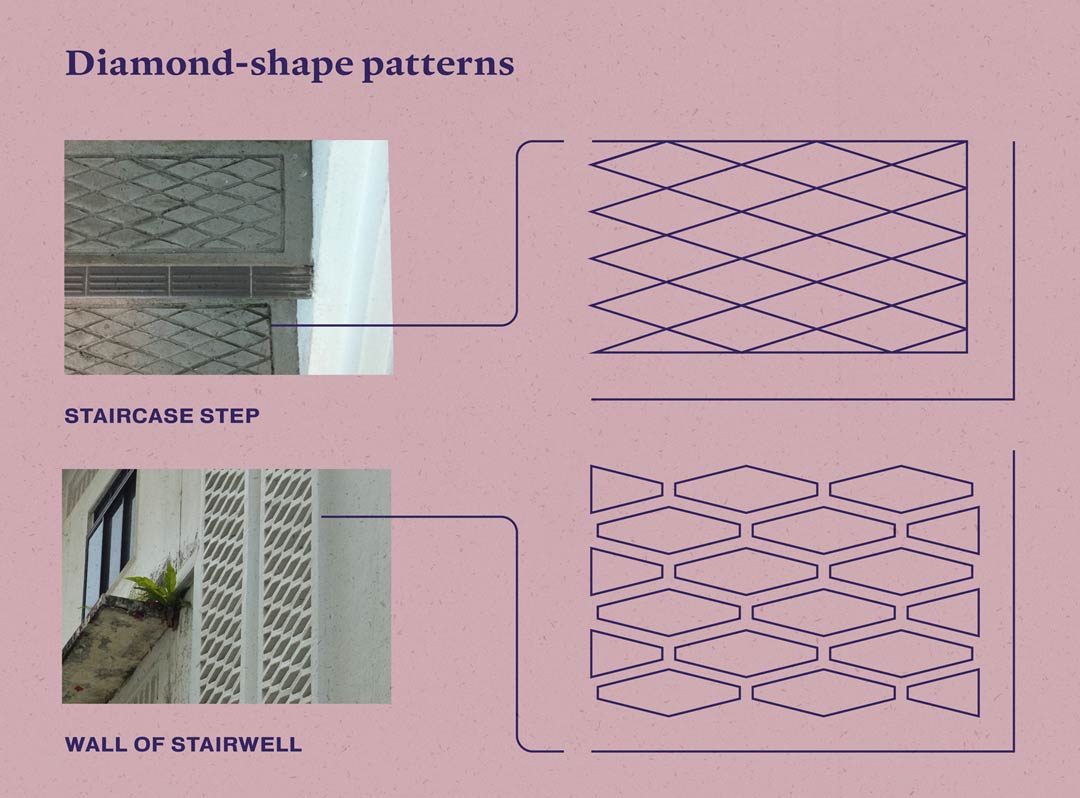

5. The Beauty of Safety

Image (top) courtesy of Studio Lapis

Another example of form following function in the former CHS is in a stairwell at the junction of the L-shaped building. To bring light and air into a staircase used by hundreds of students, precast diamond-shape blocks with vents were stacked atop of one another to create a distinctive geometric screen wall. A similar pattern was also imprinted on the staircase steps, giving them an anti-slip feature.

CHS concrete stairs were also extremely well-built to withstand fire and allow large groups of people in the building to quickly disperse during an emergency, explains Weng Hin. “The number of bars they put inside, the cement grade, everything was of very high quality because they were such an important safety feature.”

More histories behind our buildings may be uncovered as restoration work continues. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram for the latest updates on our redevelopment, upcoming events and art collection.