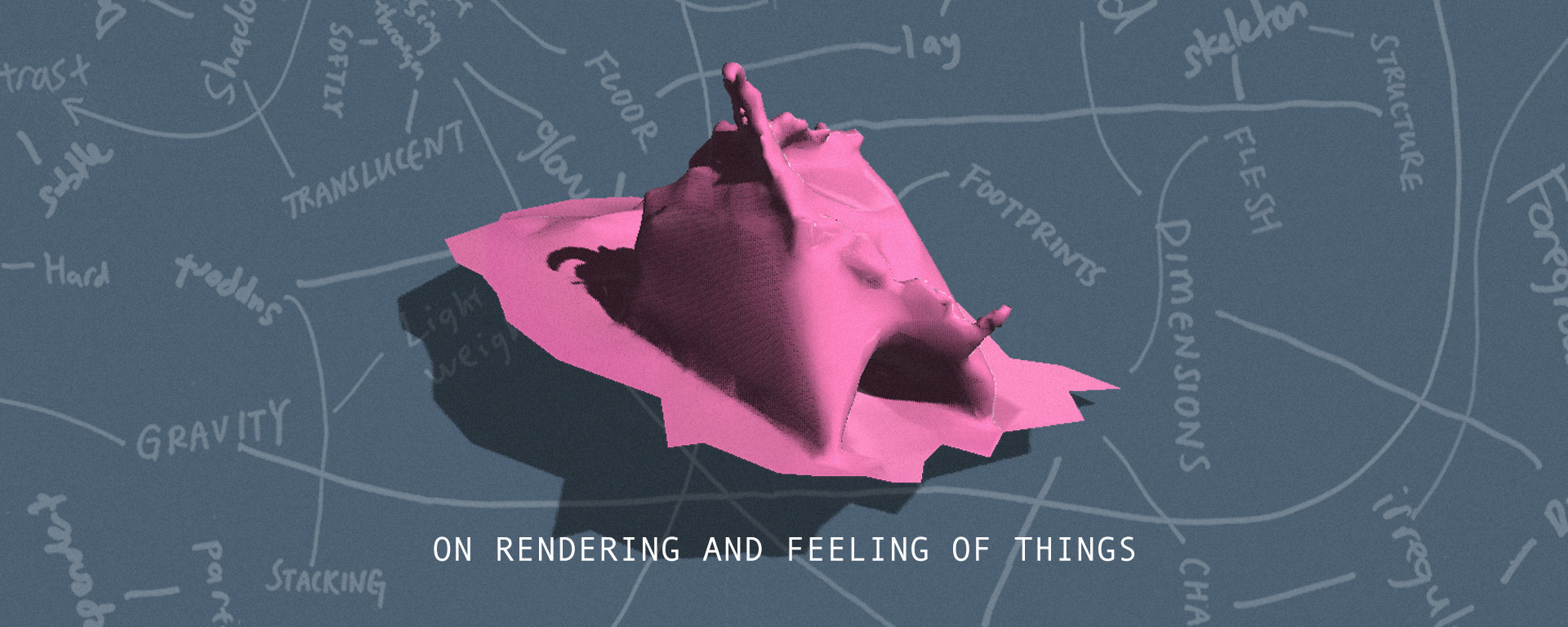

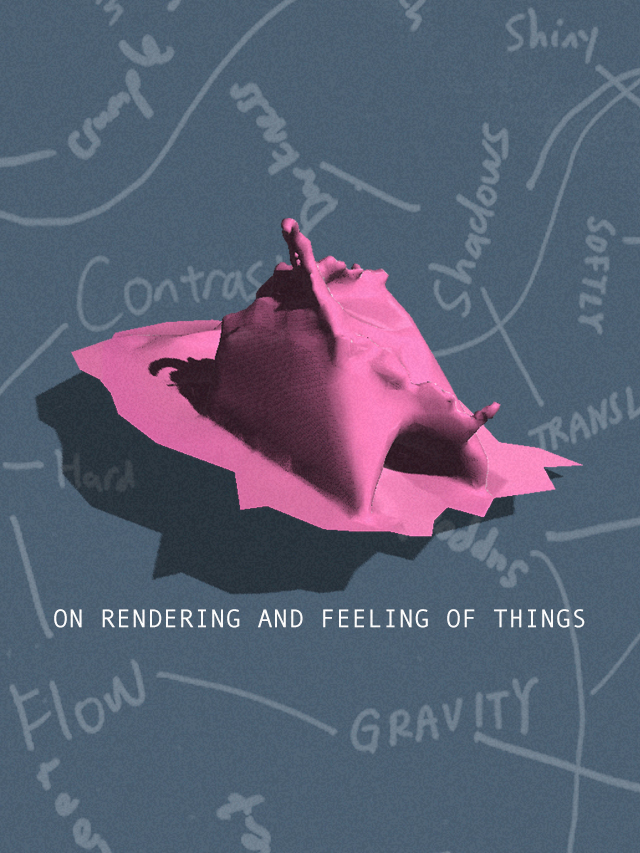

On rendering and feeling of things

In a time when the physical and digital are blurred, what skills do we need to understand and critically shape our hybrid realities? Artists are now being asked to invest in digital skills more than ever: to "upskill" and pursue "personal development," to prepare to emerge on the other side of COVID equipped for a future whose material and digital realities will be even more intertwined.

In considering the screen as a speculative medium for sculptural artworks, Skill Futures Episode 2 invited artists Aki Hassan and Rifqi Amirul to conduct a workshop, elaborating primarily on contemporary concerns and future possibilities in sculpture making.

Expanding from their ongoing collaborations, the workshop explored what digital materiality may mean as we produce sculptures under hybrid physical-digital conditions. Challenging our understanding of materiality and physicality, participants were taken through exercises involving building a speculative vocabulary for sculptures to making, rendering and translating sculptures from physical to digital forms.

Curator Syaheedah Iskandar speaks with the two artists about their intentions for the workshop and why it was important to engage in conversations with the everyday public regarding the future of sculptural making.

The workshop expanded from a collaborative project you both worked on, Falling into Its Thingness, culminating in a digital showcase. Can you share how that project came about?

Falling into its Thingness came about amid the pandemic between 2020 and 2021. We felt the sharp shift during this period, as digitalisation was normalised and expected of artists. Sculptors, installation and multidisciplinary studio-based artists like ourselves felt pressured to conform and make sense of our practices in the digital space. We realised that this was a shared concern between ourselves, thus we decided to put together this project that examines the digital space and whether it was equipped with tools to capture the sensitivities and qualities of physically made objects and re-imagine sculptural possibilities within the virtual realm.

Apart from the project being a response to the surge into digitalisation brought upon by the pandemic, two years on, as we move slowly into a post-pandemic world, are there new concerns or reflective points you’ve had since then?

Yes, of course! There are elements of the virtual space that physical works may not be able to offer. In this first iteration, the project explored the notion of gravity within digital spaces. The microsite we created offered a “ground” for us to experiment with. What does it mean for an object to ‘fall’ in a digital space? Are digital objects weightless? Our experimentations were scattered across the microsite in response to one another.

Since exploring the idea of gravity, we’ve been thinking about other kinds of capacities, such as the idea of physical space vs digital space. How large can a digital sculpture be? These concerns arose as we started thinking about the scarcity of physical space in Singapore.

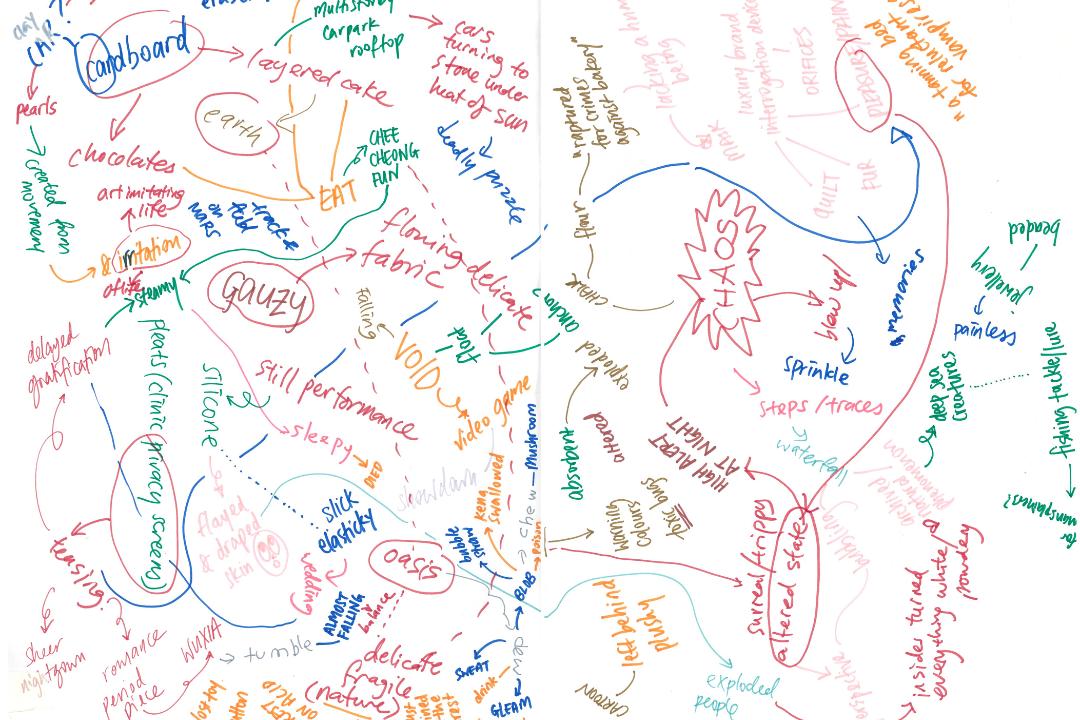

Scanned image of Vocabulary Exercise from Group 1.

Take us through the exercises you’ve conceived for the workshop. The first part of the workshop involved participants generating a critical vocabulary on speculating the experience as one sees sculptures on the screen. Why was this important?

We wanted to bring the participants through the way we think about things. Through a series of vigorous exercises, participants were invited to build their own personalised vocabulary indexes. These indexes of meanings shine on how the participants imagine, approach and make meanings based on the affects or feelings of the things they see. We did a few meaning-making exercises in the workshop through a range of mini exercises with texts, images, mind maps, and objects.

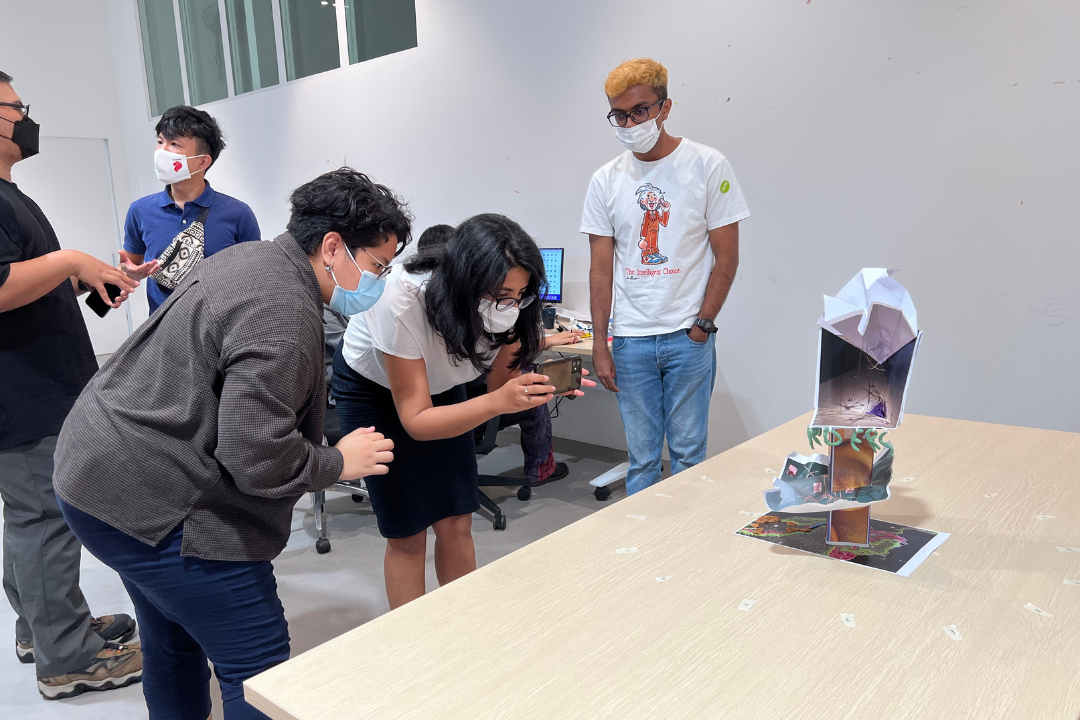

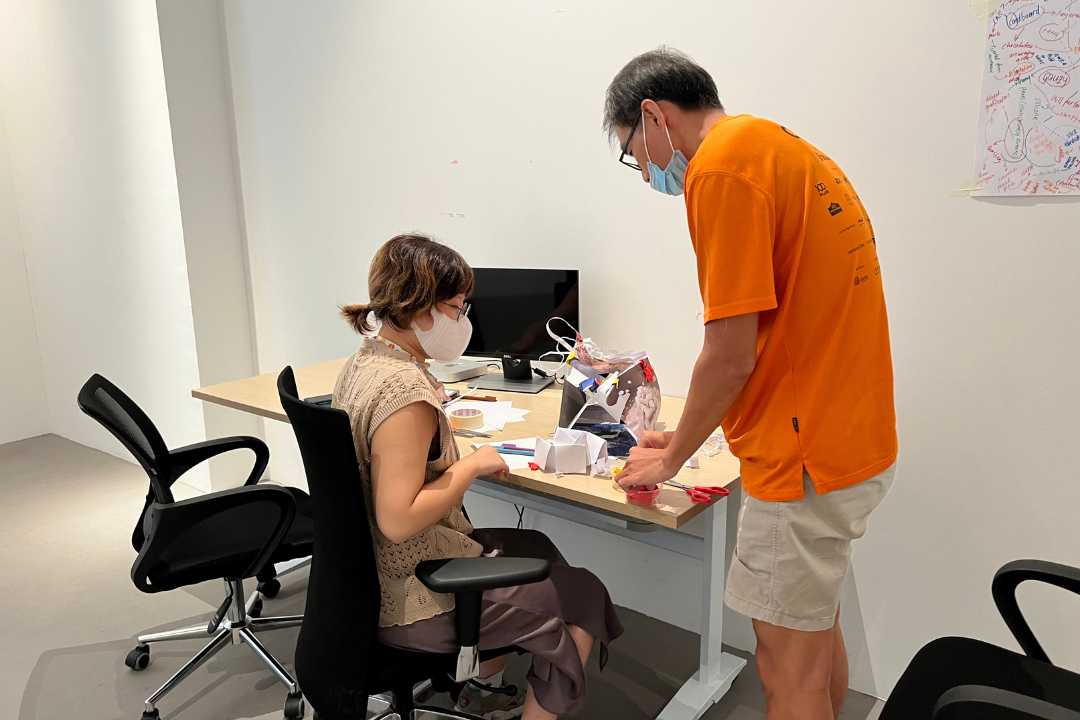

Aki guiding participants how to digitally record their sculptural objects for a smoother rendering on software.

The second part of the workshop introduces photogrammetry. Take us through this method and the thinking process. What did you both consider that characterises the relationship between the sculpture and the spatial in its digital form through this tool?

These exercises then culminated into a collective activity where they created a paper sculpture using photos they took of things they saw around the vicinity of TPD. These paper sculptures were then transformed into digital objects using a program known as Agisoft MetaShape. With this program, you can create a series of images (of the object) and a digital view of the 3D object. We felt that this aspect of the project was vital as the participants are able to visualise the process of rendering physical objects, which transforms them into digital objects. We reminded the participants to embrace the errors in the translation of physical to digital, as these “errors” likely capture the qualities that physical objects are not able to.

Participants collaboratively building paper sculptures during the workshop.

Clearly, producing digital sculptures collaboratively and hosting a workshop on these ideas produces different experiences. As the first workshop that you’ve both conducted together for the public, what were some key moments and learning points you’ve had with the participants?

We had a very wide range of ages from students to adults. It was an enriching experience for us as we got to hear many perspectives from them across their disciplines. The participants had an exciting exchange while learning a new skill of not just 3D scanning but also unlearning and relearning ways of translation, processing and thinking about things sculpturally. One of the highlights was the collaborativeness of the participants, where they had to turn 2D images into sculptural objects - this encouraged them to think collaboratively and creatively to bridge the gap between collective meaning while making a physical sculpture. Another moment was revealing our 3D scans of the objects and looking at the interesting ‘errors’ and ‘glitches’ in these scans.

On the future of sculpture-making, what are some speculations, fears, and possibilities that you both are imagining?

Aki: My fear is for us to stick to traditional ideas of what a sculpture ought to be: bulky, hefty and clear in its ability to stand. I wish for sculptural artworks to work against all odds, presenting themselves as limitless and working against real gravity.

Rifqi: Totally. I wish for sculptures to free themselves from space and weight constraints. There is a possible future in how we think about sculpture which can include an element of virtuality and/or physicality. These projects we’ve worked on help us better understand the constraints and weight of sculptural practice and establish alternative processes.

The second cycle of Skill Futures will begin with a performance by Natasha Tontey on 29 Mar. Sign up now or learn more here !